AMSTERDAM LEADERSHIP LAB - April 12, 2022Ranran Li - Recent Development in Personality Assessment

Decades of research have shown that personality traits (especially conscientiousness), combined with general mental ability and past experience, provide satisfactory job performance prediction. Furthermore, personality measures can predict job performance fairly well when the job activates the desired trait(s). Moreover, certain trait(s), when left unattended at personnel selection, can produce unintended consequences for organizations (consider employee integrity, a crucial feature for the successful functioning of organizations). Given these, it is important for organizations to incorporate personality measures during personnel selection. Indeed, personality measures have been increasingly used in the industry.

This blog touches upon some recent development in personality assessment. It is structured as follows: I first introduce how personality has been assessed traditionally, then the key part – the advent of new personality assessment approaches in this digital era. In the end, I also briefly explain problems that exist in commercialized assessment tools (most notably, MBTI) and why those shouldn’t be used for selection purposes.

TRADITIONAL PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Traditionally, personality has been assessed by either self-report personality inventories or via others’ ratings (close others, otherwise trained raters). While they tend to be convenient to administer, there are disadvantages associated with self-reported personality measures: A major shortcoming lies in its vulnerability to social desirability effects. Although personality traits represent individual differences, which are allegedly no good or bad, many traits have an implicit socially desirable direction. For instance, we assume that being conscientious, honest, proactive, and agreeable is great and can lead to desirable consequences. Thus, people may consciously or unconsciously respond in a socially desirable manner, especially in high-stake situations like job applications. A second limitation is that self-report personality measures are reliant on the information that is consciously accessible to the individual. The Johari Window model suggests that we as human beings have blind spots or insufficient insights of our own. Thus, there are always discrepancies between self- and informant reports of personality measures. This introspective limitation again threatens the validity of the information obtained via self-report instruments. Other nonnegligible caveats include but are not limited to being lengthy (more informative meaning more items are required) and less fun during administration. This leads to extra time and burden for respondents.

THE ADVENT OF NEW PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT APPROACHES IN THE DIGITAL ERA

The easily accessible digital footprints in this digital era have afforded more opportunities for collecting, processing, and analyses of high-volume data. Accordingly, machine learning approaches to personality assessments (MLPA) have emerged.

Social media text mining (SMTM) approach to personality assessment, for instance, makes use of language data extracted from various social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, personal web blogs). It has become an alternative source of information over self- or other- personality ratings. While personality assessments via machine learning algorithms have their advantages – less time-consuming, less vulnerable to cognitive limitations, etc. – many caveats also exist. First, it inevitably suffers from the biases already present in the training data (e.g., self- or other-rated personality scores are used as the ‘ground truth’). Second, data quality remains a problem. It is controversial whether social media data is sufficiently reliable and, more so, consistent across different platforms. Each social media platform is characterized by its unique features; thus, there can be substantial differences in personality-relevant information (i.e., behavior) across different platforms. Last but not least, ethical challenges exist if companies were to use job applicants’ social media text data for their personality assessment.

Another notable advance is AI-powered personality assessment. With the increasing costs of personnel selection (especially human capital costs for onsite interview), AI-powered interview has emerged, this can be either digital or pre-recorded video interview. Automated video interviews (AVIs) use either verbal (text data), paraverbal (audio data), nonverbal (facial expressions), or combinations of these in personality assessment. Our lab recently developed a word-count text-analysis technique for assessing HEXACO traits from job interviews. Further, research showed that a more construct valid personality score could be obtained when the interview questions activated the predicted trait.

Game-based assessments have also been developed in the past decade. For instance, a gamified assessment game Building Docks was developed at our lab in collaboration with the LTP business, specifically to measure the trait Honesty-Humility. Research showed that the assessment game has incremental validity beyond self-reported personality in predicting cheating for financial gain. Another example is Skyrise City, an assessment game developed by Artic Shores to assist with personnel selections; it incorporates the measure of cognition, drive, interpersonal style, etc.

Personality has also been predicted from patterns of behaviors collected passively via wearable devices. For instance, research led by Stanford University showed that various domains of behaviors collected on smartphones were distinctively predictive of personality traits. These behaviors included communication behavior, music consumption, app usage, mobility, day- and night-time, and overall phone activity.

The digital era has rendered many opportunities for the assessment of personality, yet challenges co-exist, most notably, data sources, data quality, and privacy implications.

COMMERCIAL VS. VALIDATED PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Another worthy-to-mention issue that hinders the spread of validated personality assessment tools is those popular yet controversial personality assessment tools, notably, the MBTI test. It is probably the most renowned instrument among lay people for personality assessment (e.g., in the Chinese population). However, it is problematic in many aspects.

The most notable problem is the binary classification of each dimension, which loses substantial information about the individual. Extraversion/introversion, for instance, is a single dimension that falls along continua. Each person stands somewhere on a continuum of low to high extraversion. In validated personality instruments (the Five-Factor Model or the HEXACO model of personality), respondents receive raw scores and converted standardized scores on each dimension (e.g., Stanine score or percentile rank) to learn their relative standing compared to the norm group of similar others. On the other hand, MBTI classifies respondents into binary categories on each trait dimension. While labeling into 16 types helps with interpretation to some extent, it undoubtedly loses information substantially and ignores the nonnegligible differences within the same type. Humans are complicated species with various personality profiles. On each trait continua, there are indefinite (∞) categories; even if we merely consider trait-level, say five traits, then there are ∞^5 categories, not to mention that each trait consists of sub facets that capture different aspects of the same trait.

Another major problem with the MBTI is that it completely ignores neuroticism (i.e., emotionality/emotional stability). Neuroticism is an important personality trait that is present in all validated personality models (e.g., Big Five, HEXACO). It describes how frequently one experiences negative emotions, feelings of anxiety, sadness, or vulnerability. Since neuroticism has predictive effects – on average, negative effects – on various life outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction, relationship dissolution, health outcomes), the test strategically avoids telling the respondents anything negative. The lack of important trait, together with other deficiencies (e.g., lack of grounded theory), jointly contribute to the insufficient, or rather, the poor predictive validity of the test. Personality instruments are developed not only to assist with our self-understanding, but they also have functional usages, help with personnel selection at the workplace, for instance. MBTI is not a good predictor of career outcomes, romantic relationships, health outcomes, etc. Thus, it is rather a commercialized tool.

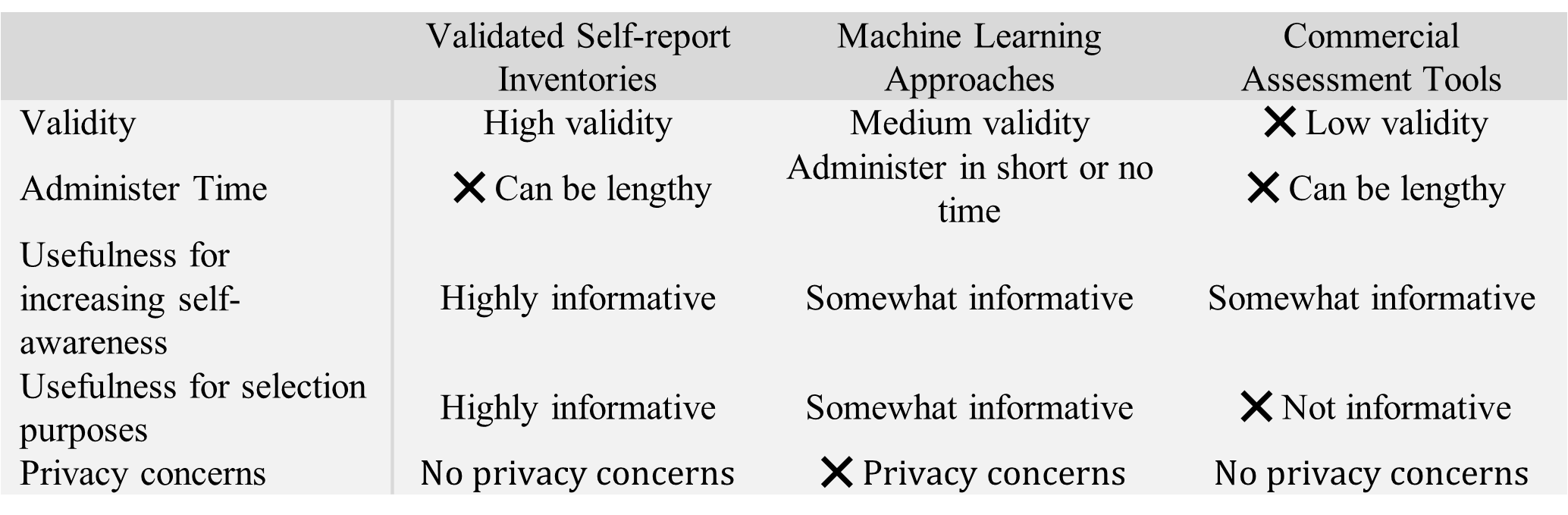

The table below displays a rough comparison between personality assessments introduced in this blog: traditional self-report inventories, machine learning approaches to personality assessment, and commercial (yet unvalidated) personality assessment tools.

Sources

Building Docks: A gamified tool for personality assessment. Retrieved from: https://www.ltp.nl/building-docks-integriteit-meten-via-een-game/

Should you trust the Myers-Briggs personality test? Retrieved from: https://areomagazine.com/2021/03/09/should-you-trust-the-myers-briggs-personality-test/

Holtrop, D., Oostrom, J. K., van Breda, W. R. J., Koutsoumpis, A., & de Vries, R. E. (2022). Exploring the application of a text-to-personality technique in job interviews. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2022.2051484

Stachl, C., Au, Q., Schoedel, R., Gosling, S. D., Harari, G. M., Buschek, D., Völkel, S. T., Schuwerk, T., Oldemeier, M., Ullmann, T., Hussmann, H., Bischl, B., & Bühner, M. (2020). Predicting personality from patterns of behavior collected with smartphones. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17680–17687. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920484117

Tay, L., Woo, S. E., Hickman, L., & Saef, R. M. (2020). Psychometric and validity issues in machine learning approaches to personality assessment: A focus on social media text mining. European Journal of Personality, 34(5), 826–844. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2290